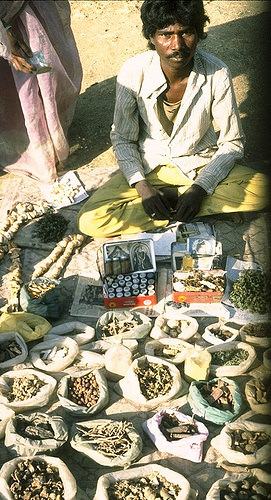

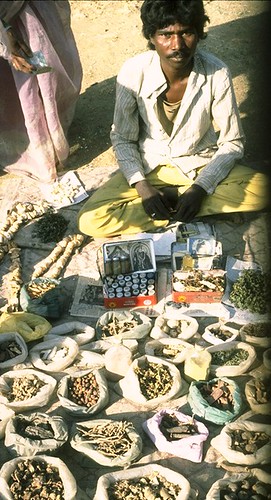

The therapeutic uses of many forest plant species, such as those pictured above in a local market in central India, are based on generations of experiences by traditional medical practitioners, and represent an important component of traditional forest knowledge. Photo by John Parrotta

People around the world manipulate ecosystems for their own purposes. It’s what you leave behind when you’re finished working or living in the area that determines whether the ecosystem survives or is irreparably harmed for future generations.

For scientists like John Parrotta, national program leader for international science issues with the U.S. Forest Service, knowing what to leave behind is not always found in a college textbook or scientific journal.

“We can do sustainability science better if we learn from traditional ecological knowledge,” Parrotta said. “These knowledge systems typically have different roots than western science. They are more holistic in their thinking.”

Traditional ecological knowledge, or TEK, does not always come from indigenous peoples such as Native American tribes. The sources for this knowledge exists in many rural communities around the globe.

People in many parts of Europe who own forests in addition to farmland have for centuries managed their trees to supply their needs for small timber, fence posts, and firewood as well as to improve wildlife habitat for hunting purposes.

“Most of the agroforestry practiced today throughout the world is rooted in traditional ecological knowledge,” Parrotta said. “Scientists have only recently translated these generations-old insights and practices into scientific language in an effort to promote these sustainable practices more widely”.

An example of agricultural practices that embody the long-range perspectives typical of traditional knowledge holders is the shifting cultivation system used for decades in the mountainous region of northeast India. Farmers there cultivate an area of forest land for a few years before moving on to a new location. Before leaving, they plant a variety of trees and shrubs to prevent erosion and help restore the soil’s nutrients. Years down the road, when they return to the area, the land is in better condition than it would be if they’d just abandoned it.

Traditional ecological knowledge is not just about food. A number of Forest Service scientists have been studying how traditional knowledge can contribute to finding sustainable solutions to pressing forest management and conservation issues. For example Frank Lake, a scientist with the agency’s Pacific Southwest Research Station in California, studies traditional fire-management practices in Oregon and gives practical recommendations to fire managers.

“This is truly innovative work that combines the best of generations-old wisdom and modern forest science,” Parrotta said.