Dado el tamaño y el crecimiento de la población hispana en los Estados Unidos y su poder adquisitivo, la comunidad hispana es un motor clave del crecimiento de los mercados nacionales de consumo, incluyendo nuestro mercado de productos orgánicos.

De parte del Programa Nacional Orgánico (NOP, por sus siglas en inglés) del Servicio de Comercialización Agrícola (AMS, por sus siglas en inglés), por favor, únase a nosotros a medida que continuamos celebrando el Mes Nacional de la Herencia Hispana. La observancia de un mes, realizada todos los años del 15 de septiembre al 15 de octubre, celebra las culturas y tradiciones de los estadounidenses que tienen sus raíces en España, México y países de habla hispana de América Central, América del Sur, y el Caribe. En el NOP, el aumentar nuestra apreciación de las culturas hispanas igual que nuestras conexiones con los hispanos es esencial para nuestro éxito.

Es mucho lo que hemos hecho y seguimos haciendo para servir participantes hispanos. Las regulaciones orgánicas del USDA, así como el Manual del Programa Nacional Orgánico – que contienen los estándares orgánicos, documentos de orientación, memorandos de política e instrucciones – están disponibles en español. Además, nuestra reciente iniciativa orgánica “Sound and Sensible,” que ayuda a que la certificación orgánica sea más accesible, alcanzable y asequible para pequeños productores y procesadores, también incluye recursos en español.

Según la Oficina de Censo de EE.UU., hoy hay más de 56.6 millones de hispanos en los Estados Unidos. Las personas de origen o descendencia hispana representan el 17.6 por ciento de la población total y constituyen el grupo más grande y uno de los de crecimiento más rápido de los grupos minoritarios étnicos o raciales. Además, según el Centro Selig para el Crecimiento Económico, el poder adquisitivo de la población hispana en los Estados Unidos se estima en aproximadamente $ 1.3 trillones, una cantidad mayor que el Producto Interno Bruto (PIB) de México, el tercer mayor socio comercial de nuestro país.

Dado el tamaño y el crecimiento de la población hispana en los Estados Unidos y su poder adquisitivo, la comunidad hispana es un motor clave del crecimiento de los mercados nacionales de consumo, incluyendo nuestro mercado de productos orgánicos. De acuerdo con un estudio realizado por la Asociación de Comercio Orgánico (OTA, por sus siglas en inglés), con el crecimiento del mercado nacional ha habido un crecimiento en la diversidad de familias que compran productos orgánicos, tal que la diversidad de consumidores empieza a alinearse con los datos étnicos y raciales del país.

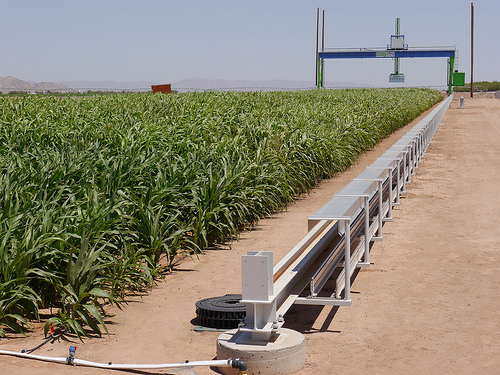

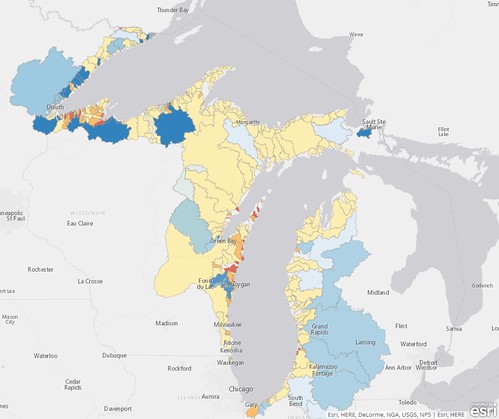

Participantes del NOP también incluyen operaciones orgánicas certificadas, tanto en los Estados Unidos como en el extranjero. De acuerdo con el Censo de Agricultura de 2012, el número de agricultores hispanos en los Estados Unidos aumentó un 21 por ciento entre 2007 y 2012. En California, el estado con el mayor número de operaciones certificadas como orgánica, la porción de agricultores de origen hispano es del 12 por ciento, cuatro veces más que el promedio nacional de 3 por ciento. En el extranjero, de acuerdo con la base de datos Organic INTEGRITY, hay más de 31,700 operaciones orgánicas certificadas a las normas del USDA. Aunque un poco más del 70 por ciento de estas operaciones se encuentran en los Estados Unidos, aproximadamente el 30 por ciento o alrededor de 9,300 de ellas están en más de 120 países extranjeros. De las que están en el extranjero, casi el 60 por ciento están en España, México y países de habla hispana de América Central, América del Sur, y el Caribe.

Fortaleciendo nuestras relaciones con participantes hispanos en el extranjero, estamos trabajando con México en un acuerdo bilateral de equivalencia orgánica, y esperamos añadir a México a nuestra lista de socios de comercio internacional. Además, estamos trabajando con el Instituto Interamericano de Cooperación para la Agricultura (IICA) y su Comisión Interamericana de Agricultura Orgánica (CIAO) en el desarrollo del sector orgánico en América Latina.

Por lo tanto, el celebrar el Mes de la Herencia Hispana es una celebración no sólo de las diversas culturas y las personas que componen los Estados Unidos sino también una celebración de nuestros clientes nacionales e internacionales. Y, al exitosamente honrar y servir a nuestros clientes, nuestro programa tiene éxito.