Centennial Job Corps camp crew cleaning hose returned from the fire line. Forest Service photo

In the back parking lot of the National Interagency Fire Center (NIFC), seven workers wear neon green shirts with the Camp Crew logo written across the back.

And they stand out.

They are young and their bright T-shirts contrast with those of the more seasoned personnel. As the crew works among large mounds of fire hose spread throughout the lot, it’s obvious they have one thing on their mind: meticulously preparing the hose for the next fire.

As the camp crew works to support the fire operations, military veteran Loren VanHorn supports them as the Camp Crew Boss.

Five years ago, VanHorn was exploring retirement options after serving 20 years in the military when a former supervisor and friend mentioned the Centennial Job Corps in Nampa, Idaho. He’s been with Centennial ever since.

Centennial Job Corps’ Loren VanHorn leads a Camp Crew at the National Interagency Fire Center. Forest Service photo

“My job and goal is to prepare and mentor these students for the challenges of fire support assignments, working in a stressful environment as a team, and supporting them in-part with the skill sets I learned in the military: leadership, honor and a work ethic,” VanHorn said.

For the 2016 fire season, the Boise National Forest worked with the Center to hire four retired military veterans to oversee two Camp Crews consisting of ten students each. These veterans bring command presence, leadership, solid work ethic and the ability to make decisions under stress. They serve as excellent student mentors for future career ambitions.

The Centennial Job Corps program has several trade programs for all students including carpentry, welding and nursing. Camp Crews also work at Incident Command Posts providing support to the logistic sections and have even helped radio technicians on incidents.

Centennial Job Corps drying fire hose in preparation for the next fire. Forest Service photo

Forest Service Centennial Job Corps Assistant Fire Management Officer, Mike Towers says that students in the Job Corps Fire Program are looked up to by the Centennial student body.

“They all know that their peers who volunteer for the program demonstrate integrity, solid work ethics, making decisions under stress, and serve as excellent mentors,” said Towers. “Having retired veterans is an added bonus and we are very fortunate to have them as Camp Crew Bosses.”

“I am extremely proud of all of these students and veterans and their contribution to the success of the Centennial Job Corps Camp Crews,” Towers said. “Together they are a testament to hard work, determination, with a willingness to succeed and are the true back bone to the success of the Centennial Job Corps camp crews.”

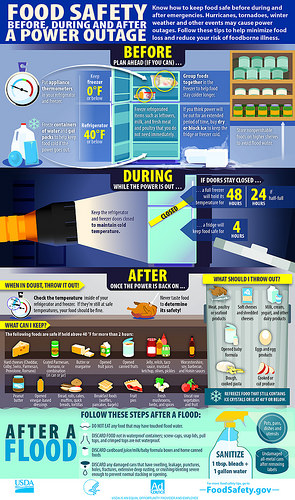

Because September is National Preparedness Month, it is a good time to think about emergency planning. Don’t Wait. Communicate. Make an Emergency Communication Plan for you and your family because you just don’t know when disasters will impact your community.

Used fire house at the Pioneer Fire. Forest Service photo