MyPlate has new resources for families working together toward a healthier lifestyle.

It’s that time again…back-to-school season is upon us. It’s an exciting time of year for kids, offering a new beginning with the promise of new friends and new experiences. It’s also a great time for families to establish a new routine and work together toward a healthier lifestyle. ChooseMyPlate.gov and Team Nutrition just launched new resources to help your family eat better together, including printable activity sheets, tips for making mealtimes fun and stress-free, and videos featuring real families who share healthy eating solutions that work for them.

For example, meet Lilac and PJ. See how this family of five (and grandma too) makes healthy eating work, while incorporating their Laotian heritage and adjusting to the addition of a new baby.

Every family is unique. When it comes to healthy eating, choose a starting place that works for your family, whether it’s going to a farmers market together or letting kids plan your next healthy dinner menu. Visit ChooseMyPlate.gov/Families for more ideas to get kids of all ages involved in planning healthy family meals:

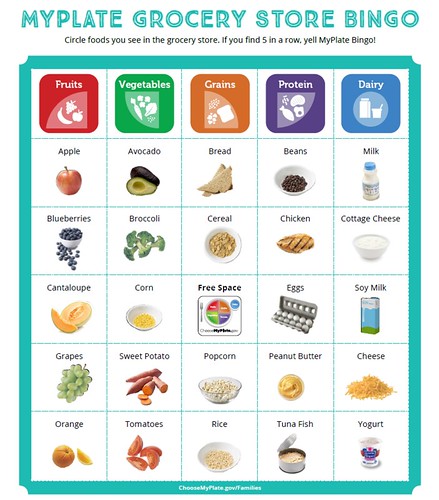

- For younger children, try our MyPlate Grocery Store Bingo game during your next shopping trip. Kids can learn about the food groups while you shop.

- If your kids are picky eaters, try the MyPlate Food Critic activity to expose them to new flavors. In this activity, kids are empowered to pick out and rate a new food.

- For tweens and teens, the Kid’s Restaurant activity lets kids be the chef by planning and preparing a meal for their parents.

MyPlate Grocery Store Bingo is a great activity for kids accompanying mom or dad on a grocery shopping trip.

And when it comes to healthy eating at school, the USDA’s Team Nutrition initiative has a number of free Back-to-School resources, including:

- MyPlate Guide to School Lunch and MyPlate Guide to School Breakfast

These one-page handouts discuss how school meals help kids meet their nutritional needs and support learning.

- Welcome to School Lunch!

This handout for kindergarten parents introduces kids to school lunch and provides an activity for children to sort lunch foods into the five food groups. It also includes a “Color Adventure” challenge where families taste-test new fruits and vegetables of different colors.

- What You Can Do To Help Prevent Wasted Food

This booklet discusses ways to reduce, recover, and recycle food before it goes to waste. Get ideas for your school by reading tips for school nutrition professionals, teachers, parents, students, and school administrators.

- A Guide To Smart Snacks in Schools

This colorful booklet provides an overview of Smart Snacks Standards and how to tell if a food and beverage meets the requirements. This is a ready-to-go resource for anyone that oversees the sale of foods/beverages to students on the school campus during the school day.

For more healthy eating tips and resources, sign up for MyPlate email updates and the Team Nutrition E-Newsletter.

The new MyPlate Guide to School Lunch discusses how school meals help kids meet their nutritional needs and support learning.