The basic facts about the global increase of CO2 in our atmosphere are clear and established beyond reasonable doubt. Nevertheless, I’ve recently seen some of the old myths peddled by “climate skeptics” pop up again. Are the forests responsible for the CO2 increase? Or volcanoes? Or perhaps the oceans?

Let’s start with a brief overview of the most important data and facts about the increase in the carbon dioxide concentration in the atmosphere:

- Since the beginning of industrialization, the CO2 concentration has risen from 280 ppm (the value of the previous millennia of the Holocene) to now 405 ppm.

- This increase by 45 percent (or 125 ppm) is completely caused by humans.

- The CO2 concentration is thus now already higher than it has been for several million years.

- The additional 125 ppm CO2 have a heating effect of 2 watts per square meter of earth surface, due to the well-known greenhouse effect – enough to raise the global temperature by around 1 °C until the present.

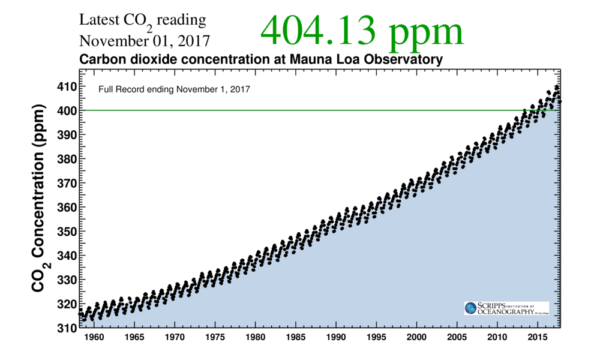

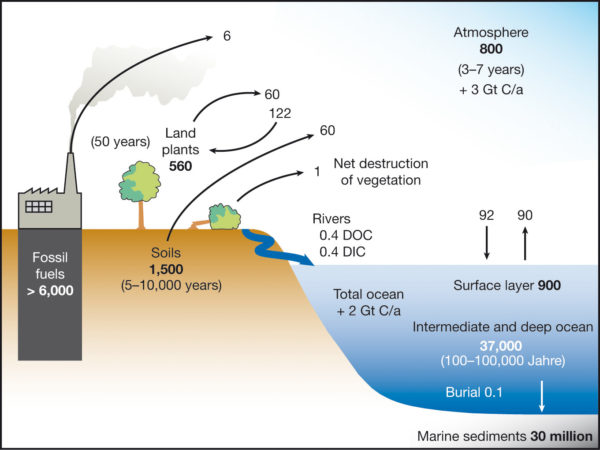

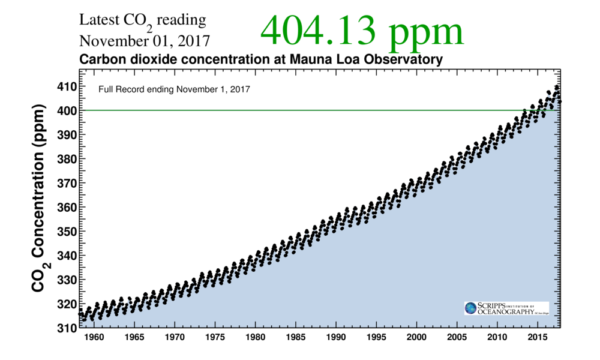

Fig. 1 Perhaps the most important scientific measurement series of the 20th century: the CO2 concentration of the atmosphere, measured on Mauna Loa in Hawaii. Other stations of the global CO2 measurement network show almost exactly the same; the most important regional variation is the greatly subdued seasonal cycle at stations in the southern hemisphere. This seasonal variation is mainly due to the “inhaling and exhaling” of the forests over the year on the land masses of the northern hemisphere. Source (updated daily): Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

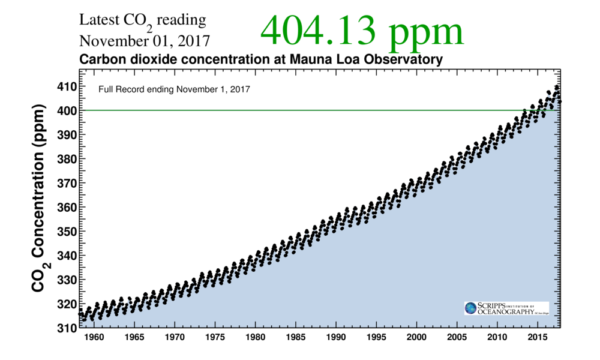

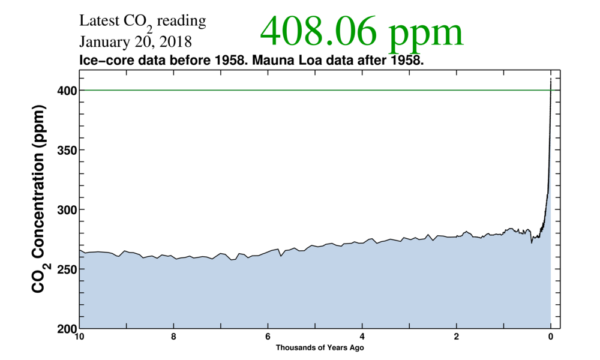

Fig. 2 The CO2 concentration of the atmosphere during the Holocene, measured in the ice cores from Antarctica until 1958, afterwards Mauna Loa. Source: Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

These facts are well known and easy to understand. Nevertheless, I am frequently confronted with attempts to play down the dangerous CO2-increase, e.g. recently in the right-leaning German newspaper Die Welt.

Are the forests to blame?

Die Welt presented a common number-trick by climate deniers (readers can probably point to some english-language examples):

In fact, carbon dioxide, which is blamed for climate warming, has only a volume share of 0.04 percent in the atmosphere. And of these 0.04 percent CO2, 95 percent come from natural sources, such as volcanoes or decomposition processes in nature. The human CO2 content in the air is thus only 0.0016 percent.

The claim “95 percent from natural sources” and the “0.0016 percent” are simply wrong (neither does the arithmetic add up – how would 5% of 0.04 be 0.0016?). These (and similar – sometimes you read 97% from natural sources) numbers have been making the rounds in climate denier circles for many years (and have repeatedly been rebutted by scientists). They present a simple mix-up of turnover and profit, in economic terms. The land ecosystems have, of course, a high turnover of carbon, but (unlike humans) do not add any net CO2 to the atmosphere. Any biomass which decomposes must first have grown – the CO2 released during rotting was first taken from the atmosphere by photosynthesis. This is a cycle. Hey, perhaps that’s why it’s called the carbon cycle!

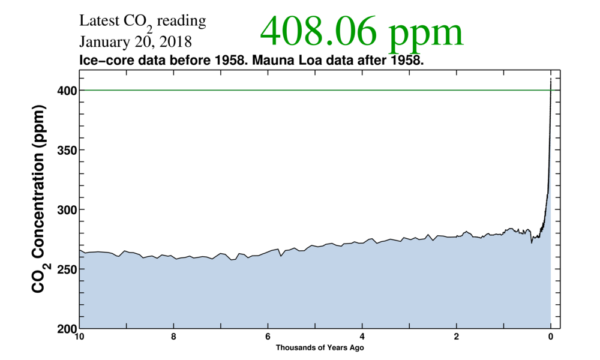

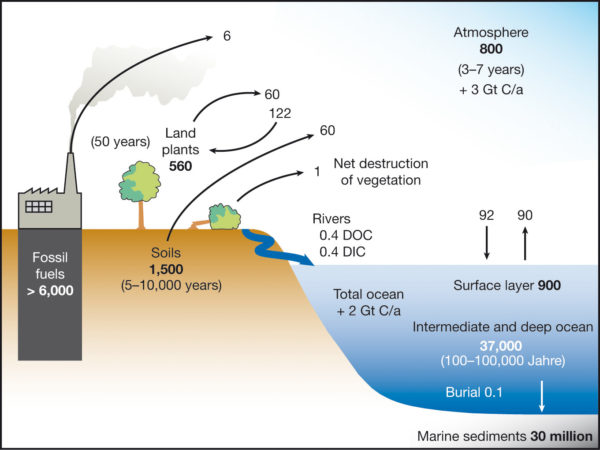

That is why one way to reduce emissions is the use of bioenergy, such as heating with wood (at least when it’s done in a sustainable manner – many mistakes can be made with bioenergy). Forests only increase the amount of CO2 in the air when they are felled, burnt or die. This is immediately understood by looking at a schematic of the carbon cycle, Fig. 3.

Fig. 3 Scheme of the global carbon cycle. Values for the carbon stocks are given in Gt C (ie, billions of tonnes of carbon) (bold numbers). Values for average carbon fluxes are given in Gt C per year (normal numbers). Source: WBGU 2006 . (A similar graph can also be found at Wikipedia.) Since this graph was prepared, anthropogenic emissions and the atmospheric CO2 content have increased further, see Figs 4 and 5, but I like the simplicity of this graph.

If one takes as the total emissions a “natural” part (60 GtC from soils + 60 GtC from land plants) and the 7 GtC fossil emissions as anthropogenic part, the anthropogenic portion is about 5% (7 of 127 billion tons of carbon) as cited in the Welt article. This percentage is highly misleading, however, since it ignores that the land biosphere does not only release 120 GtC but also absorbs 122 GtC by photosynthesis, which means that net 2 GtC is removed from the atmosphere. Likewise, the ocean removes around 2 GtC. To make any sense, the net emissions by humans have to be compared with the net uptake by oceans and forests and atmosphere, not with the turnover rate of a cycle, which is an irrelevant comparison. And not just irrelevant – it becomes plain wrong when that 5% number is then misunderstood as the human contribution to the atmospheric CO2 concentration.

The natural earth system thus is by no means a source of CO2 for the atmosphere, but it is a sink! Of the 7 GtC, which we blow into the atmosphere every year, only 3 remain there. 2 are absorbed by the ocean and 2 by the forests. This means that in the atmosphere and in the land biosphere and in the ocean the amount of stored carbon is increasing. And the source of all this additional carbon is the fact that we extract loads of fossil carbon from the earth’s crust and add it to the system. That’s already clear from the fact that we add twice as much to the atmosphere as is needed to explain the full increase there – that makes it obvious that the natural Earth system cannot possibly be adding more CO2 but rather is continually removing about half of our CO2 emissions from the atmosphere.

The system was almost exactly in equilibrium before humans intervened. That is why the CO2 concentration in the air was almost constant for several thousand years (Figure 2). This means that the land ecosystems took up 120 GtC and returned 120 GtC (the exact numbers don’t matter here, what matters is that they are the same). The increased uptake of CO2 by forests and oceans of about 2 GtC per year each is already a result of the human emissions, which has added enormous amounts of CO2 to the system. The ocean has started to take up net CO2 from the atmosphere through gas exchange at the sea surface: because the CO2 concentration in the atmosphere is now higher than in the surface ocean, there is net flux of CO2 into the sea. And because trees take up CO2 by photosynthesis and can do this more easily if you offer them more CO2 in the air, they have started to photosynthesize more and thus take up a bit more CO2 than is released by decomposing old biomass. (To what extent and for how long the land biosphere will remain a carbon sink is open to debate, however: this will depend on the extent to which the global ecosystems come under stress by global warming, e.g. by increasing drought and wildfires.)

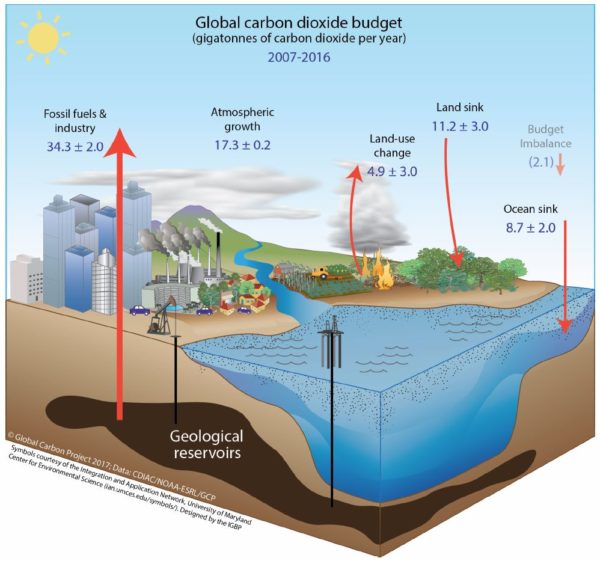

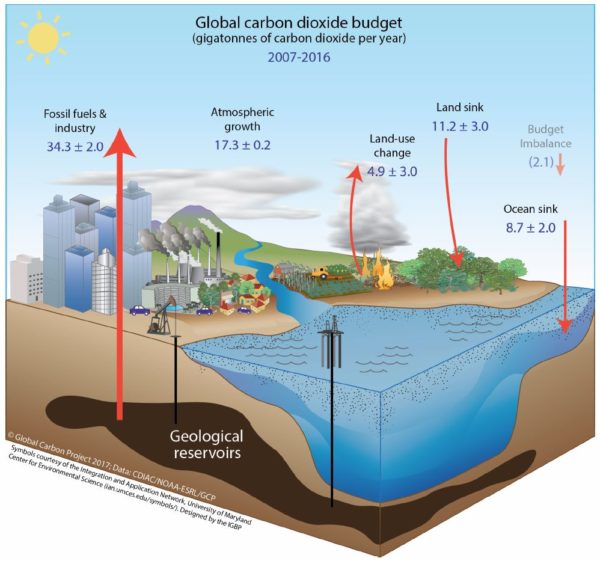

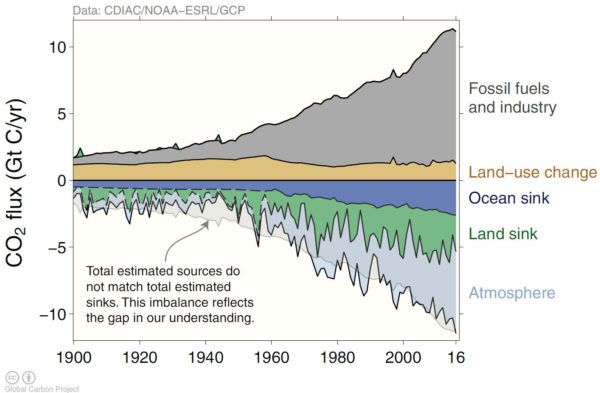

The next diagram shows (with more up-to-date and accurate numbers) the net fluxes of CO2 (this time in CO2 units, not carbon units!).

Fig. 4 CO2 budget for 2007-2016, showing the various net sources and sinks. The figures here are expressed in gigatons of CO2 and not in gigatons of carbon as in Fig. 3. The conversion factor is 44/12 (molecular weight of CO2 divided by atomic weight of carbon). Source: Global Carbon Project.

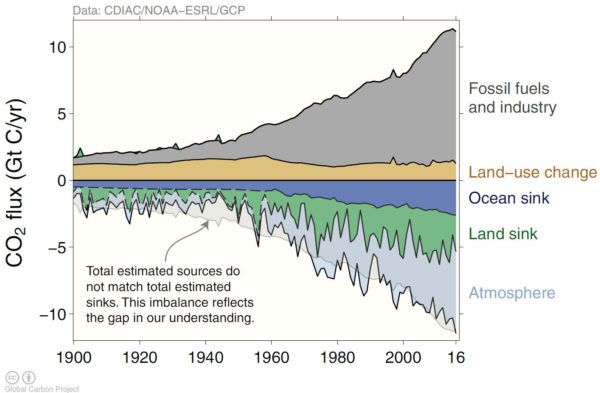

Fig. 5 shows where the CO2 comes from (in the upper half you see the sources – fossil carbon and deforestation) and where it ends up (in the lower half you sees the sinks), in the course of time. It ends up in comparably large parts in air, oceans and forests. The share absorbed by the land ecosystems varies greatly from year to year, depending on whether there were widespread droughts, for example, or whether it was a good growth year for the forests. That is why the annual CO2 increase in the atmosphere also varies greatly each year, and this short-term variation is not mainly caused by variations in our emissions (so a record CO2 increase in the atmosphere in an El Niño year does not mean that human emissions have surged in that year).

Fig. 5 Annual emissions of carbon from fossil sources and deforestation, and annual emissions from the biosphere, atmosphere and ocean (the latter are negative, meaning net uptake). This is again in carbon (not CO2) units; the 12 gigatons of carbon emitted in 2016 are a lot more than the 7 gigatons in the older Fig. 3. Source: Global Carbon Project.

The “climate skeptics” blaming the forests for most of the increase in atmospheric CO2, because of decaying foliage and deadwood, is not merely wrong, it is pretty bonkers. Have leaves started to decompose only since industrialization? Media with a minimum aspiration to credibility should clearly reject such nonsense, instead of spreading it further. In case of Die Welt, one of my PIK colleagues had explicitly pointed out to the author, in response to a query by him, that the 5% human share of CO2 is misleading and that humans have caused a 45% increase. That the complete CO2 increase is anthropogenic has been known for decades. The first IPCC report, published in 1990, put it thus:

Since the industrial revolution the combustion of fossil fuels and deforestation have led to an increase of 26% in carbon dioxide concentration in the atmosphere.

In the 27 years since then, the CO2 increase caused by our emissions has gone up from 26% to 45%.

How Exxon misled the public against better knowledge

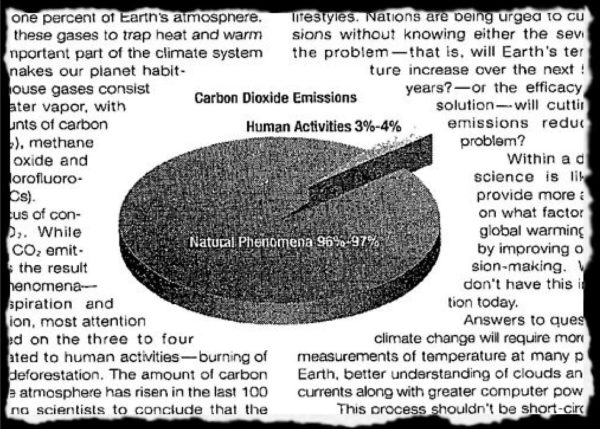

One fascinating question is where this false idea of humans just contributing a tiny bit to the relentless rise in atmospheric CO2 has come from? Have a look at this advertorial (a paid-for editorial) by ExxonMobil in the New York Times from 1997:

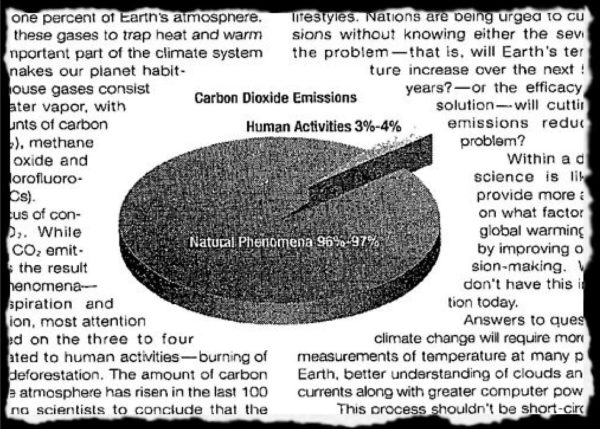

Fig. 6 Excerpt from the New York Times of 6 November 1997

The text to go with it read:

While most of the CO2 emitted by far is the result of natural phenomena – namely respiration and decomposition, most attention has centered on the three to four percent related to human activities – burning of fossil fuels, deforestation.

That is pretty clever and could hardly be an accident. The impression is given that human emissions are not a big deal and only responsible for a small percentage of the CO2 increase in the atmosphere – but without explicitly saying that. In my view the authors of this piece knew that this idea is plain wrong, so they did not say it but preferred to insinuate it. A recent publication by Geoffrey Supran und Naomi Oreskes in Environmental Research Letters has systematically assessed ExxonMobil’s climate change communications during 1977–2014 and found:

We conclude that ExxonMobil contributed to advancing climate science—by way of its scientists’ academic publications—but promoted doubt about it in advertorials. Given this discrepancy, we conclude that ExxonMobil misled the public.

They explain their main findings in this short video clip.

Does the CO2 come from volcanoes?

Another age-old climatic skeptic myth, is that the CO2 is coming from volcanoes – first time I had to rebut this was as a young postdoc in the 1990s. The total volcanic emissions are between 0.04 and 0.07 gigatonnes of CO2 per year, compared to the anthropogenic emissions of 12 gigatons in 2016. Anthropogenic emissions are now well over a hundred times greater than volcanic ones. The volcanic emissions are important for the long-term CO2 changes over millions of years, but not over a few centuries.

Does the CO2 come from the ocean?

As already mentioned and shown in Figs. 4 and 5, the oceans absorb net CO2 and do not release any. The resulting increase in CO2 in the upper ocean is documented and mapped in detail by countless ship surveys and known up to a residual uncertainty of + – 20% . This is, in itself, a very serious problem because it leads to the acidification of the oceans, since CO2 forms carbonic acid in water. The observed CO2 increase in the world ocean disproves another popular #fakenews piece of the “climate skeptics”: namely that the CO2 increase in the atmosphere might have been caused by the outgassing of CO2 from the ocean as a result of the warming. No serious scientist believes this.

Remember also from Figs. 4 and 5 that we emit about twice as much CO2 as is needed to explain the complete rise in the atmosphere. In case you have not connected the dots: the denier myth of the oceans as cause of the atmospheric CO2 rise most often comes in the form of “the CO2 rise lagged behind temperature rise in glacial cycles”. It is true that during ice ages the oceans took up more CO2 and that is why there was less in the atmosphere, and during the warming at the end of glacial cycles that CO2 came back out of the ocean, and this was an important amplifying feedback. But it is a fallacy to conclude that the same natural phenomenon is happening again now. As I explained above: measurements clearly prove that the modern CO2 rise has a different cause, namely our fossil fuel use. What is the same now and over past glacial cycles is not the CO2 source, but the greenhouse effect of the atmospheric CO2 changes: without that we could not understand (or correctly simulate in our climate models) the full extent of glacial cycles.

The cyanide cocktail

A man offers you a cocktail with a little bit of cyanide at a party. You reject that indignantly, but the man assures you it is completely safe: after all, the amount of cyanide in your body after this drink would be only 0.001 percent! This could hardly be harmful! Those scientists who claim that 3 mg cyanide per kg of body weight (ie 0.0003 percent) are fatal are obviously not to be trusted. Are you falling for that argument?

We hope not, and we hope you will neither fall for the claim that 0.0125 percent of CO2 (that’s the 125 ppm increase caused by humans) can’t be bad because that number is small. Of course, the amount of CO2 in the air could also be expressed in kilograms: it is 3200 billion tons or 3,200,000,000,000,000 kilograms. Of this humans are responsible for almost 1000 billion tons. (Does that sound more harmful than 0.0125 percent?) Since the year 1870, we have even emitted a total of about 2,000 billion tons. As already explained, forests and oceans have removed about half of that from the atmosphere.

Scientists specify the concentration of individual gases in the atmosphere as volume fractions (rather than, e.g., grams per cubic meter of air) because then the numbers do not depend on temperature and pressure, which vary greatly in the atmosphere. As far as climatic impact is concerned, however, the fraction of the total mass of the atmosphere is irrelevant since the atmosphere consists of 99.9% nitrogen, oxygen and argon, i.e. gases which cannot absorb infrared radiation. Only molecules made of at least three atoms absorb heat radiation and thus only such trace gases makes the greenhouse effect, and among these CO2 is the second most important after water vapor. All this has been known since John Tyndall’s measurements of the greenhouse effect of various gases in 1859. Tyndall back then wrote:

[T]he atmosphere admits of the entrance of the solar heat, but checks its exit; and the result is a tendency to accumulate heat at the surface of the planet.

That is still a great concise description of the greenhouse effect! Without CO2 in the air our planet would be completely frozen, no life would be possible. With CO2, we are turning one of the major control knobs of global climate.

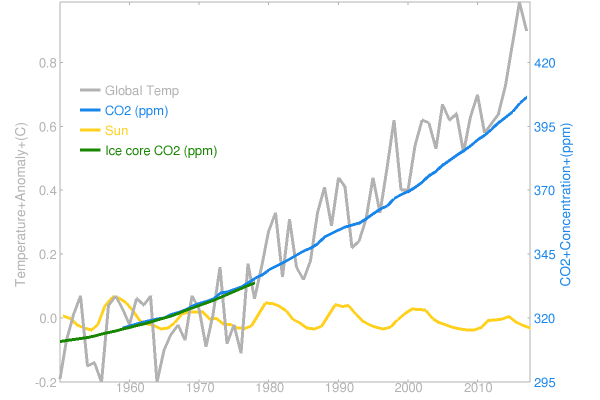

The climate effect

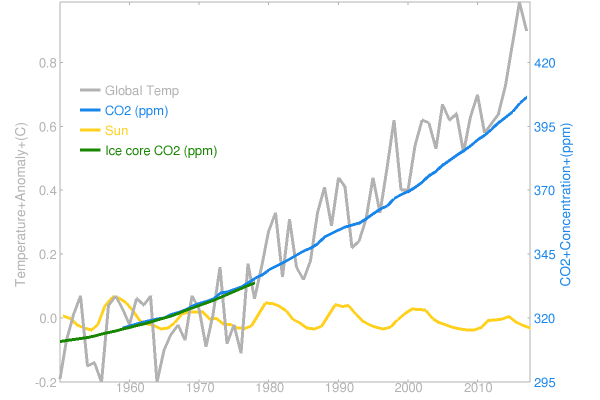

So let’s finally come to the climatic effect of the CO2 increase. As for cyanide, the effect is what counts, and not whether compared to some large mass the fraction is 10 percent or 0.01 percent. The dose effect of toxins on humans can be determined from experience with victims. The climatic impact of greenhouse gases can either be calculated on the basis of an understanding of the physical processes, or it can be determined from the experience of climate history (see my previous post). Both come to the same conclusion. The climate sensitivity (global warming in equilibrium after CO2 doubling) is around 3 °C, and the expected warming to date, due to the current CO2 increase, is around 1 °C. This corresponds quite exactly to the observed global warming (Fig. 7). For which, by the way, there is no natural explanation, and the best estimate for the anthropogenic share of global warming since 1950 is 110 percent – more on this in my previous post.

Fig. 7 Time evolution of global temperature, CO2 concentration and solar activity. Temperature and CO2 are scaled relative to each other as the physically expected CO2 effect on the climate predicts (i.e. best estimate of the climate sensitivity). The amplitude of the solar curve is scaled as derived from the observed correlation of solar and temperature data. (Details are explained here ). This graph can be created here and you can copy a code that can be used as a widget in any website (as in my home page), where it is automatically updated every year with the latest data. Thanks to Bernd Herd who programmed this.

Finally, here is a slick new video clip illustrating the history of CO2 emissions on the map:

Links

Physics Today: The carbon cycle in a changing climate

If enacted, the Administration’s FY 2019 budget proposal would have a significant negative impact on the health and resiliency of our nation’s forests.

If enacted, the Administration’s FY 2019 budget proposal would have a significant negative impact on the health and resiliency of our nation’s forests.