One of the most common questions that arises from analyses of the global surface temperature data sets is why they are almost always plotted as anomalies and not as absolute temperatures.

There are two very basic answers: First, looking at changes in data gets rid of biases at individual stations that don’t change in time (such as station location), and second, for surface temperatures at least, the correlation scale for anomalies is much larger (100’s km) than for absolute temperatures. The combination of these factors means it’s much easier to interpolate anomalies and estimate the global mean, than it would be if you were averaging absolute temperatures. This was explained many years ago (and again here).

Of course, the absolute temperature does matter in many situations (the freezing point of ice, emitted radiation, convection, health and ecosystem impacts, etc.) and so it’s worth calculating as well – even at the global scale. However, and this is important, because of the biases and the difficulty in interpolating, the estimates of the global mean absolute temperature are not as accurate as the year to year changes.

This means we need to very careful in combining these two analyses – and unfortunately, historically, we haven’t been and that is a continuing problem.

Reanalysis Analysis

Let me illustrate this with some results from the various reanalyses out there. For those of you unfamiliar with these projects, “reanalyses” are effectively the weather forecasts you would have got over the years if we had modern computers and models available. Since weather forecasts (the “analyses”) have got much better over the years because computers are faster and models are more skillful. But if you want to track the real changes in weather, you don’t want to have to worry about the models changing. So reanalyses were designed to get around that by redoing all the forecasts over again. There is one major caveat with these products though, and that is that while the model isn’t changing over time, the input data is and there are large variations in the amount and quality of observations – particularly around 1979 when a lot of satellite observations came on line, but also later as the mix and quality of data has changed.

Now, the advantage of these reanalyses is that they incorporate a huge amount of observations, from ground stations, the ocean surface, remotely-sensed data from satellites etc. and so, in theory, you might expect them to be able to give the best estimates of what the climate actually is. Given that, here are the absolute global mean surface temperatures in five reanalysis products (ERAi, NCEP CFSR, NCEP1, JRA55 and MERRA2) since 1980 (data via WRIT at NOAA ESRL). (I’m using Kelvin here, but we’ll switch to ºC and ºF later on).

Surprisingly, there is a pretty substantial spread in absolute temperatures in any one year (about 0.6K on average), though obviously the fluctuations are relatively synchronous. The biggest outlier is NCEP1 which is also the oldest product, but even without that one, the spread is about 0.3K. The means over the most recent climatology period (1981-2010) range from 287.2 to 287.7K. This range can be compared to an estimate from Jones et al (1999) (derived solely from surface observations) of 287.1±0.5 K for the 1961-1990 period. A correction for the different baselines suggests that for 1981-2010, Jones would also get 287.4±0.5K (14.3±0.5ºC, 57.7±0.9ºF)- in reasonable agreement with the reanalyses. NOAA NCEI uses 13.9ºC for the period 1901-2000 which is equivalent to about 287.5K/14.3ºC/57.8ºF for the 1981-2010 period, so similar to Jones and the average of the reanalyses.

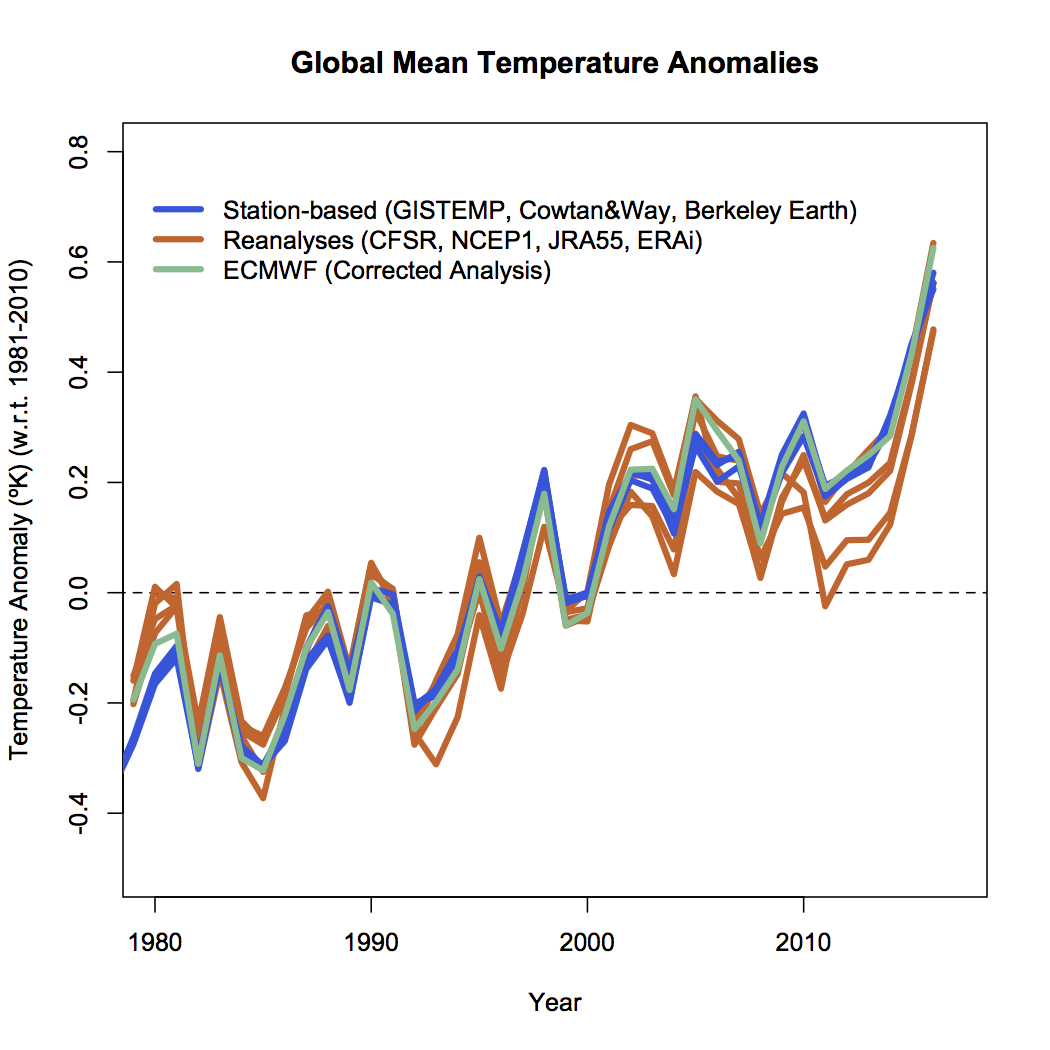

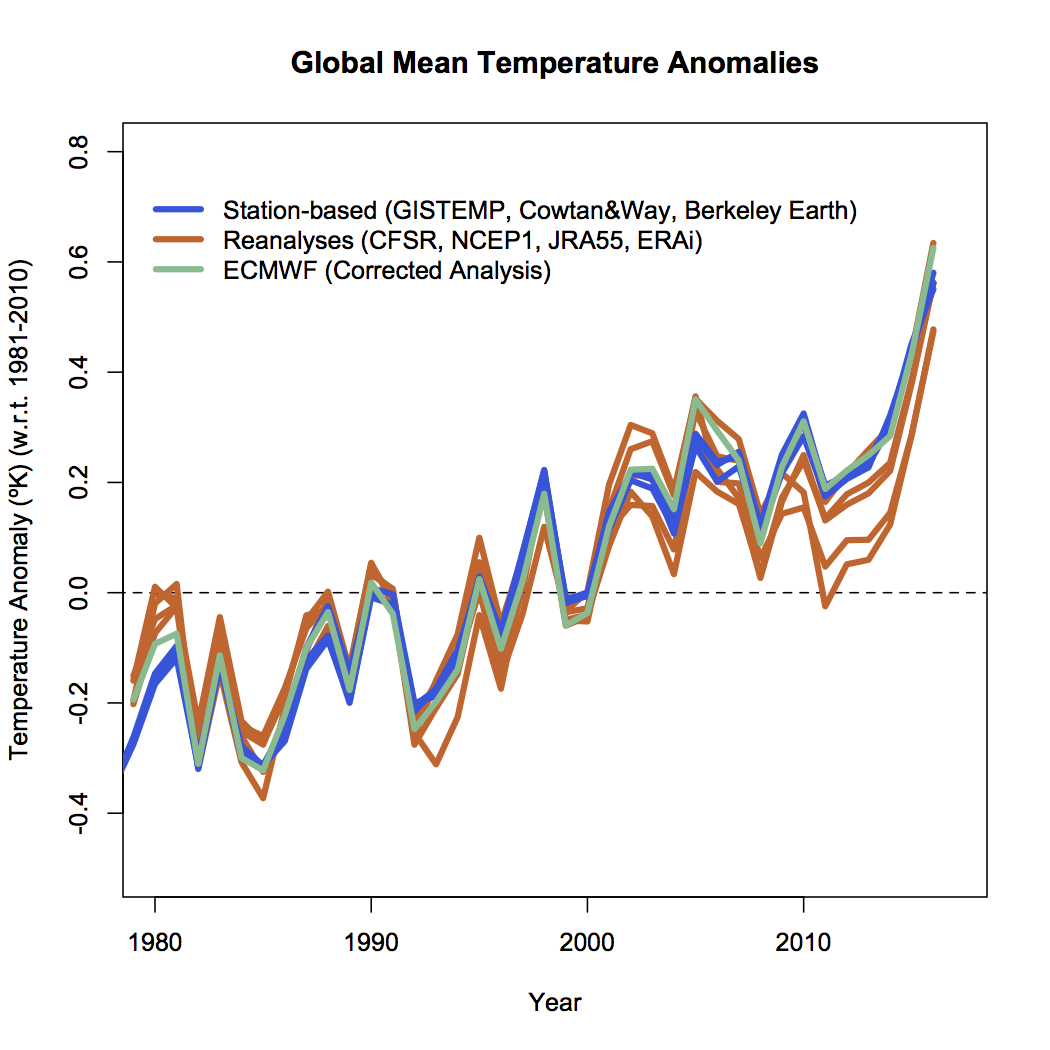

Plotting these temperatures as anomalies (by removing the mean over a common baseline period) (red lines) reduces the spread, but it is still significant, and much larger than the spread between the observational products (GISTEMP, HadCRUT4/Cowtan&Way, and Berkeley Earth (blue lines)):

Note that there is a product from ECMWF (green) that uses the ERAi reanalysis with adjustments for non-climatic effects that is in much better agreement with the station-based products. Compared to the original ERAi plot, the adjustments are important (about 0.1ºK over the period shown), and thus we can conclude that uncritically using the unadjusted metric from any of the other reanalyses is not wise.

In contrast, the uncertainty in the station-based anomaly products are around 0.05ºC for recent years, going up to about 0.1ºC for years earlier in the 20th century. Those uncertainties are based on issues of interpolation, homogenization (for non-climatic changes in location/measurements) etc. and have been evaluated multiple ways – including totally independent homogenization schemes, non-overlapping data subsets etc. The coherence across different products is therefore very high.

Error propagation

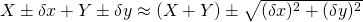

A quick aside. Many people may remember error propagation rules from chemistry or physics classes, but here they again. The basic point is that when adding two uncertain numbers, the errors add in quadrature i.e.

Most importantly, this means uncertainties can’t get smaller by adding other uncertain numbers to them (obvious right?). A second important rule is that we shouldn’t quote more precision than the uncertainties allow for. So giving 3 decimal places when the uncertainty is 0.5 is unwarranted, as is more than one significant figure in the uncertainty.

Combine harvesting

So what can we legitimately combine, and what can’t we?

So what can we legitimately combine, and what can’t we?

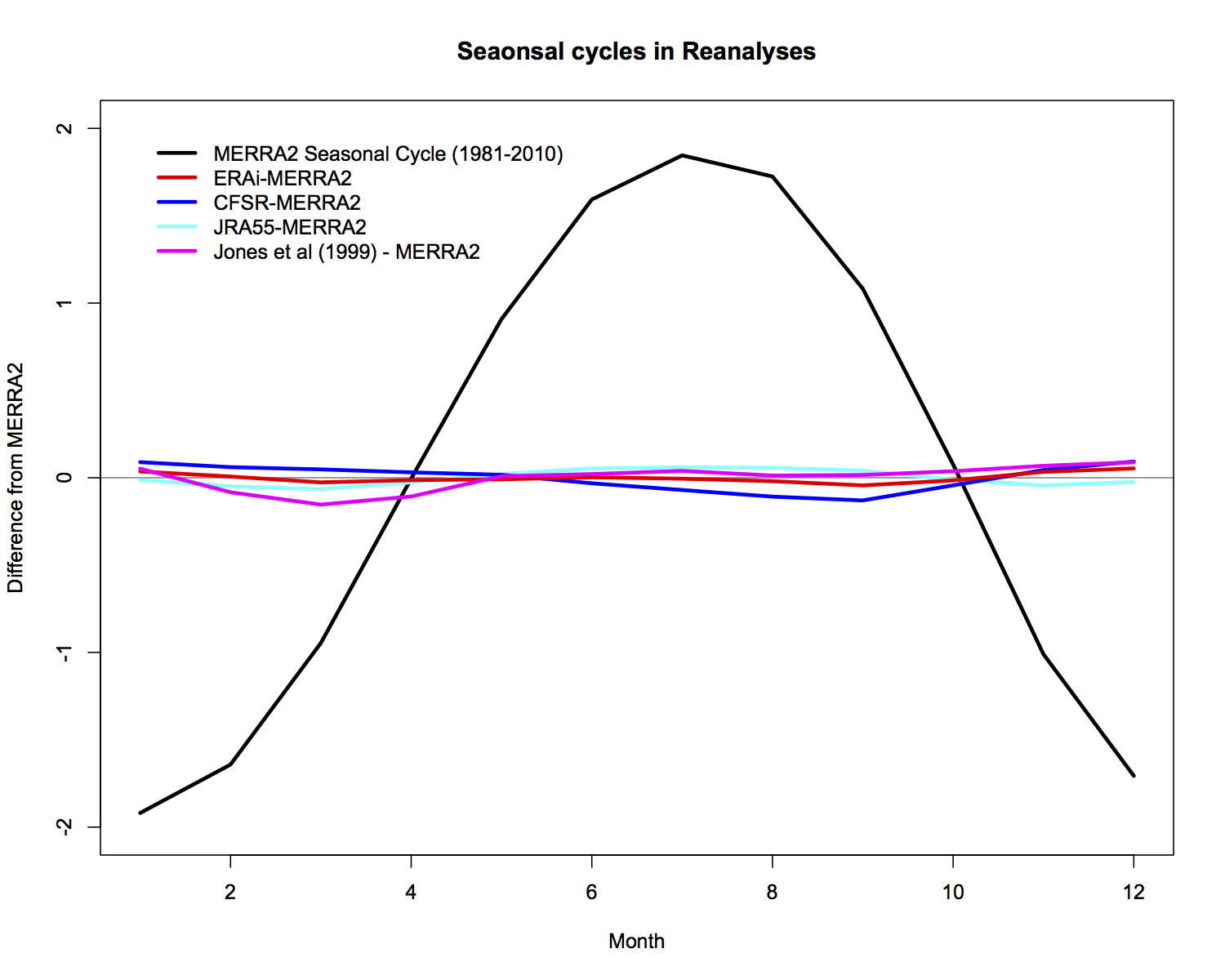

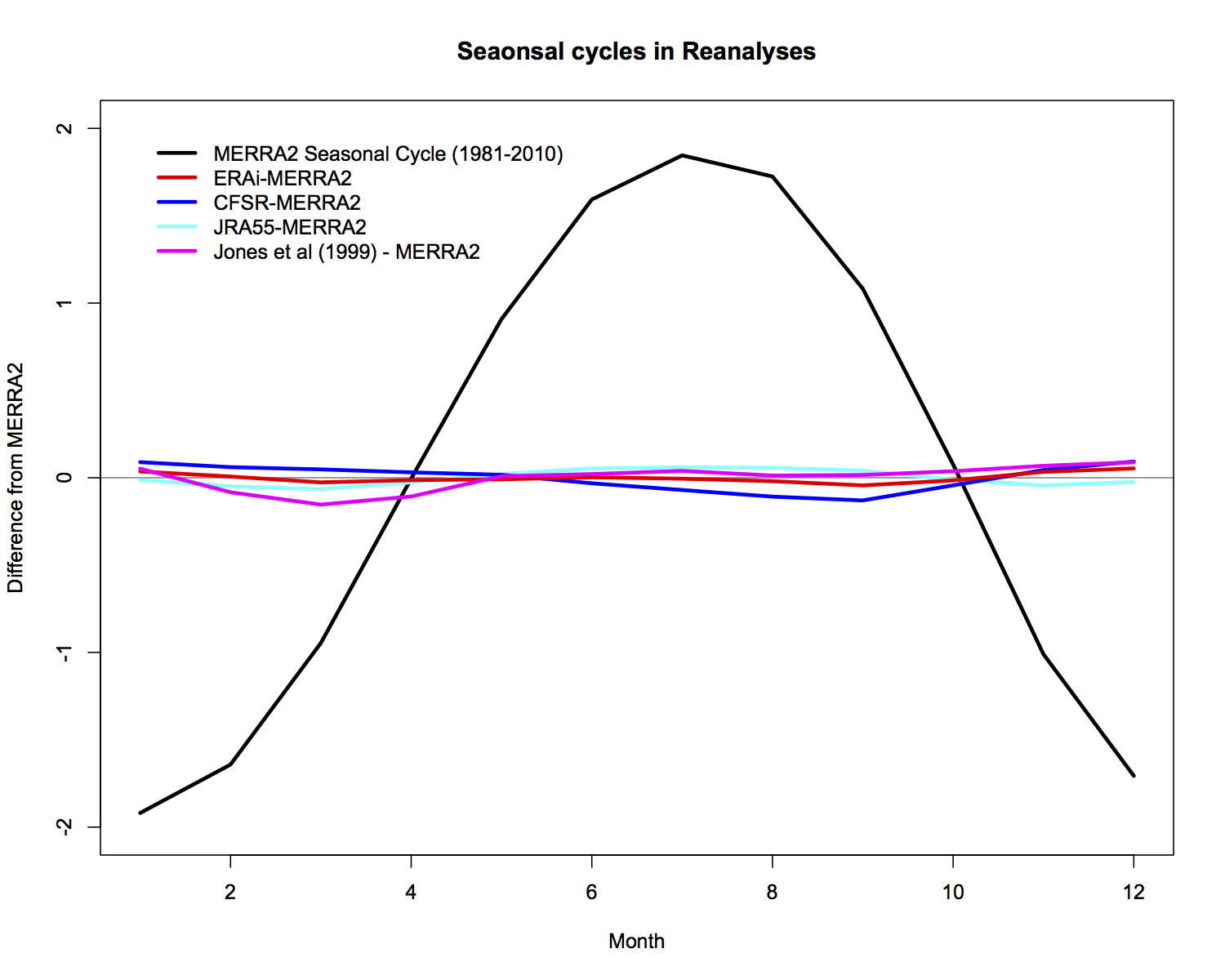

Perhaps surprisingly, the spread in the seasonal cycle in the reanalyses is small once the annual mean has been removed. This is the basis for the combined seasonal anomaly plots that are now published on the GISTEMP website. The uncertainties when comparing one month to another are slightly larger than for the anomalies for a single month, but the shifts over time are still robust.

But think about what happens when we try and estimate the absolute global mean temperature for, say, 2016. The climatology for 1981-2010 is 287.4±0.5K, and the anomaly for 2016 is (from GISTEMP w.r.t. that baseline) 0.56±0.05ºC. So our estimate for the absolute value is (using the first rule shown above) is 287.96±0.502K, and then using the second, that reduces to 288.0±0.5K. The same approach for 2015 gives 287.8±0.5K, and for 2014 it is 287.7±0.5K. All of which appear to be the same within the uncertainty. Thus we lose the ability to judge which year was the warmest if we only look at the absolute numbers.

Now, you might think this is just nit-picking – why not just use a fixed value for the climatology, ignore the uncertainty in that, and give the absolute temperature for a year with the precision of the anomaly? Indeed, that has been done a lot. But remember that for a number that is uncertain, new analyses or better datasets might give a new ‘best estimate’ (hopefully within the uncertainties of the previous number) and this has happened a lot for the global mean temperature.

Metaphor alert

Imagine you want to measure how your child is growing (actually anybody’s child will do as long as you ask permission first). A widespread and accurate methodology is to make marks on a doorpost and measure the increments on a yearly basis. I’m not however aware of anyone taking into account the approximate height above sea level of the floor when making that calculation.

Nothing disappears from the internet

Like the proverbial elephant, the internet never forgets. And so the world is awash with quotes of absolute global mean temperatures for single years which use different baselines giving wildly oscillating fluctuations as a function of time which are purely a function of the uncertainty of that baseline, not the actual trends. A recent WSJ piece regurgitated many of them, joining the litany of contrarian blog posts which (incorrectly) claim these changes to be of great significance.

One example is sufficient to demonstrate the problem. In 1997, the NOAA state of the climate summary stated that the global average temperature was 62.45ºF (16.92ºC). The page now has a caveat added about the issue of the baseline, but a casual comparison to the statement in 2016 stating that the record-breaking year had a mean temperature of 58.69ºF (14.83ºC) could be mightily confusing. In reality, 2016 was warmer than 1997 by about 0.5ºC!

Some journalists have made the case to me that people don’t understand anomalies, and so they are forced to include the absolute temperatures in their stories. I find that to be a less-than-persuasive argument for putting in unjustifiably accurate statements in the text. The consequences for the journalists may be a slightly easier time from their editor(?), but the consequences for broader scientific communication on the topic are negative and confusing. I doubt very much that this was the intention.

Conclusion

When communicating science, we need to hold ourselves to the same standards as when we publish technical papers. Presenting numbers that are unjustifiably precise is not good practice anywhere and over time will come back to haunt you. So, if you are ever tempted to give or ask for absolute values for global temperatures with the precision of the anomaly, just don’t do it!

References

P.D. Jones, M. New, D.E. Parker, S. Martin, and I.G. Rigor, “Surface air temperature and its changes over the past 150 years”, Reviews of Geophysics, vol. 37, pp. 173-199, 1999. http://dx.doi.org/10.1029/1999RG900002

So what can we legitimately combine, and what can’t we?

So what can we legitimately combine, and what can’t we?

Emily Russell has joined our development team with many new plans about how to connect people to important conservation issues. She brings extensive nonprofit experience to our mission, and we couldn’t be more excited! Read more to find out what makes Emily tick.

Emily Russell has joined our development team with many new plans about how to connect people to important conservation issues. She brings extensive nonprofit experience to our mission, and we couldn’t be more excited! Read more to find out what makes Emily tick.