By Melanie Friedel, American Forests

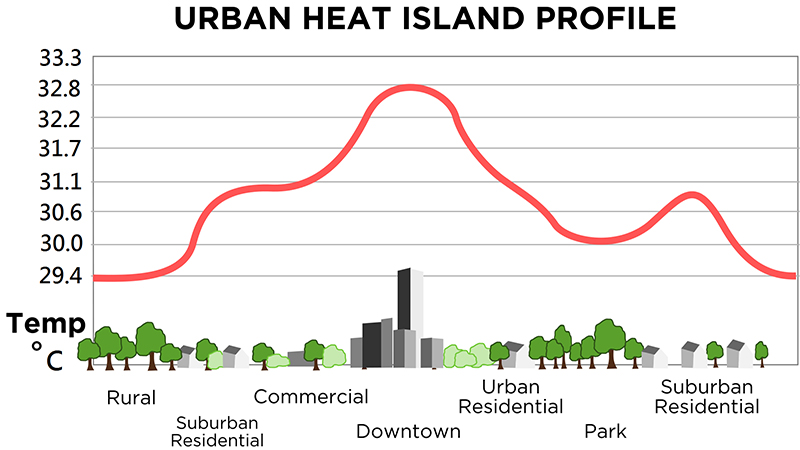

I grew up in the suburbs of Philadelphia, and for some reason, I always felt like the day got hotter as soon as I entered the city. And it wasn’t all in my imagination! There is a phenomenon called the urban heat island effect that causes urban areas to be a few degrees warmer than the surrounding rural or suburban areas, creating an “island” of concentrated heat. This happens year round, day and night. The average annual air temperature of a city with a population of 1 million or more people can be 1.8–5.4°F warmer than its surroundings. At night, this difference can be as large as 22°F warmer in cities.

That’s a pretty big disparity. So, how does it happen? First, we need to understand that objects and surfaces absorb and reflect light: darker surfaces absorb more light and lighter surfaces absorb significantly less, as they reflect a larger percentage of it. When a surface absorbs light, that light turns into thermal energy and is sent back out into the environment as heat. Thus, the more light a surface absorbs, the more heat it emits.

A temperature profile of an urban setting — notice the disparity between the pavement and the plants.

When cities are built, vegetation and green spaces are replaced by asphalt and buildings that make cities full of black surfaces like rooftops, paved streets and parking lots. These dark surfaces consequently absorb light and emit lots of heat into the city. In the most extreme urban settings, the heat gets trapped in the city by what we call the “canyon effect.” City buildings are tall and close together, and the streets are narrow, causing the heat to be held within and between buildings. The small amount of heat that is able to escape upwards ends up getting trapped between the walls of tall skyscrapers.

Many cities are like deserts: they have minimal vegetation, and their surfaces are largely impermeable to rain. This combination prevents evapotranspiration (which is essentially leaves sweating out moisture), which normally reduces temperatures by increasing the water content of the surrounding air. Not to mention, lots of heat from all the activity of people, cars, buses, trains and the burning of fossil fuels creates waste heat: heat that is emitted when people or machines use up energy. Many cities are full of waste heat before the heat island effect even begins. (Ever wonder why a crowded room feels so much hotter than one with only a few people?)

So, cities will be a few degrees warmer; doesn’t seem like such a big deal, right? Wrong. Urban heat islands do much more than just create an unpleasantly hot environment. They increase energy consumption and air conditioning costs. They also worsen air pollution, greenhouse gas emissions, water quality, heat-related illnesses and mortality.

How do they do this? Urban environments are already full of pollution from vehicles and industry. But with dark surfaces and city buildings creating and trapping heat, pollutants become even more concentrated. Buildings also act as obstacles that prevent wind flow and thereby slow the process of pollution dispersion. City ground levels often experience smog (a hazy, pollutant-packed combination of smoke and fog that lingers over cities). This creates a small scale greenhouse effect by trapping greenhouse gases from the city’s fossil fuel emissions (transportation, energy use and industry) and holding heat down at ground level and inside the city. All of these pollutants are a risk to human health, especially respiratory and cardiovascular systems, and these effects are only made worse when concentrated in a hot urban island.

When it comes to water quality, increased temperatures warm the local streams and other water bodies, disrupting the environments of and often killing native aquatic species that are used to cooler water temperatures. This disrupts the rest of the ecosystem that relies on that water.

Credit: Brett Weinstein

The process is cyclical. As the city gets hotter, the demand for air conditioning gets higher, and more energy is used, creating more heat and more pollution emissions, and higher and higher temperatures.

Thankfully, there are ways we can slow down the cycle and attempt to break it.

Painting white or light colored structure in cities will help reflect light instead of absorbing it. Planting trees and vegetation, especially green roofs and trees that cover dark pavement and trap pollutants, will help lower the concentration of CO2 in the air and cool the city. And, of course, it’s always smart to use energy efficient appliances to reduce our emissions of both pollutants and heat.

It is important that city governments work to prevent and reverse heat islands by taking these steps, but communities and individuals play a powerful role too and should implement cleaner, greener, and cooler strategies into their lives. Even with the heat island effect, cities are cool places to be. Let’s try to keep them that way.

Dr. Roslynn Brain McCann is a Sustainable Communities Extension Specialist in the Department of Environment and Society, College of Natural Resources at Utah State University. She uses conservation theory, communication techniques, and social marketing tools to foster environmental behaviors in the areas of land (conservation, reducing, reusing and recycling), air (quality and climate change), food (consuming locally with a focus on CSA’s and farmer’s markets), water (quality, quantity, water resilient landscaping), and energy (efficiency and renewable energy). Roslynn also teaches communicating sustainability, chairs the National Network for Sustainable Living Education, helps facilitate the National Extension Sustainability Summit, runs a national database of sustainability-focused Extension programs, and is the coordinator for Utah Farm-Chef-Fork, the USU Permaculture Initiative, and Sustainable You! kids’ camps.

Dr. Roslynn Brain McCann is a Sustainable Communities Extension Specialist in the Department of Environment and Society, College of Natural Resources at Utah State University. She uses conservation theory, communication techniques, and social marketing tools to foster environmental behaviors in the areas of land (conservation, reducing, reusing and recycling), air (quality and climate change), food (consuming locally with a focus on CSA’s and farmer’s markets), water (quality, quantity, water resilient landscaping), and energy (efficiency and renewable energy). Roslynn also teaches communicating sustainability, chairs the National Network for Sustainable Living Education, helps facilitate the National Extension Sustainability Summit, runs a national database of sustainability-focused Extension programs, and is the coordinator for Utah Farm-Chef-Fork, the USU Permaculture Initiative, and Sustainable You! kids’ camps.