Can a rising sea level can act as a boost for glaciers calving into the sea and trigger a surge of ice into the oceans? I finally got round to watch the documentary Chasing Ice over the Christmas and New Year’s break, and it made a big impression. I also was left with this question after watching it.

There is a connection between the unfolding events in the polar regions and our lives. The sea level may rise in jumps and spurts as a consequence of events where ice masses surge into the oceans. A sea level rise will affect a number of megacities, low lying parts of Florida, and properties along the coast of Norway: Storm surges will cause larger inundation and more damage.

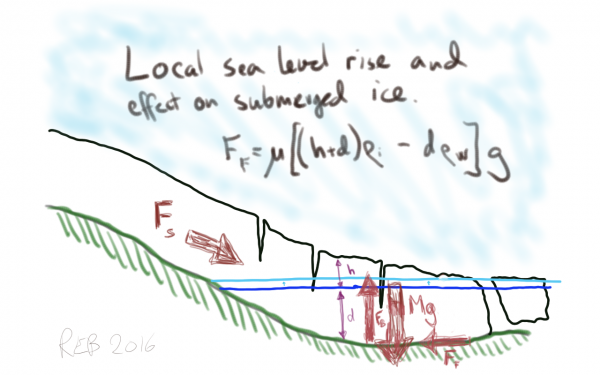

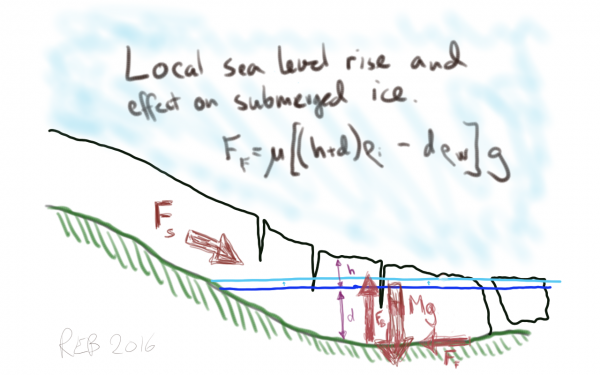

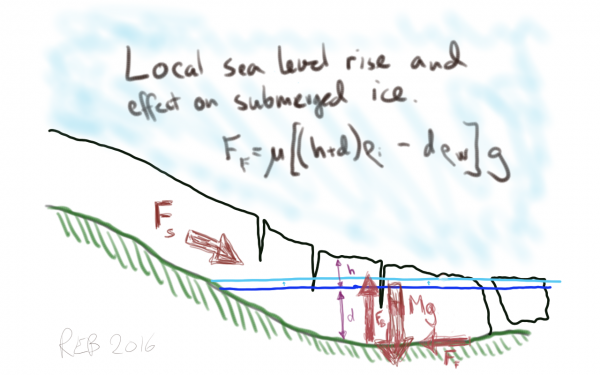

The question whether there are mechanisms that may speed up the sea level rise is therefore relevant for many people. One plausible scenario can be sketched as a balance of forces (graphics below).

At the moment, this is just a speculation from my side. I don’t know if it’s even plausible. My simple back-of-the-envelope description provides a naive picture, and it is possible that any such effect is very marginal compared to warm water intrusion. Or that the sea level rise is too small to have any noticeable effect. But I don’t know the answer yet.

There are some fruitful ways to satisfy my curiosity, and the first thing should be to search reliable bodies of knowledge. I want to be able to trace the information back to their roots, which means that sources are based on transparency and can be replicated by others.

There are some great resources for finding the best information on ice and climate change: The Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP) Snow Water Ice and Permafrost in the Arctic (SWIPA; AMAP, 2011) and the recent IPCC assessment report (AR5) chapters four and thirteen. Both these reports provide a review and assessment of the scientific literature relevant to my question. They also include proper references.

In none of these was I able to find an account of any feedback effect from rising sea levels on the flow of the ice sheets and glaciers.

I have found that there exist reports about effects which intrusion of warm seawater may have on submerged ice (eg Holland et al. 2008). There is also a number of studies about the contribution of glacier calving to the global sea level (eg Meier et al. 2007).

There was some information that almost seemed to be relevant for my question was the following passages from AR5 [13.4.3.1 “Surface Mass Balance Change”, p. 1167]:

The main feedbacks between climate and the ice sheet arise from changes in ice elevation, atmospheric and ocean circulation, and sea-ice distribution.

But ice elevation is not the same as sea level, and is relevant for glaciers mass-balance connected to snow accumulation and melting.

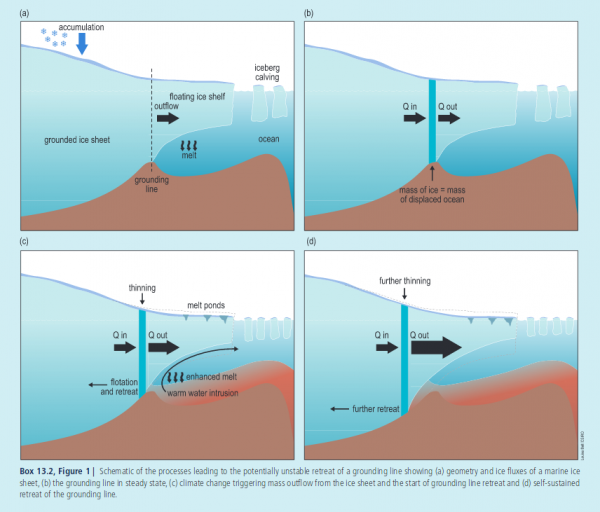

Another section from AR5 discusses the marine ice sheet instability (MISI), which is relevant to my question [13.4.4.2 “Dynamical Change”, p. 1174]:

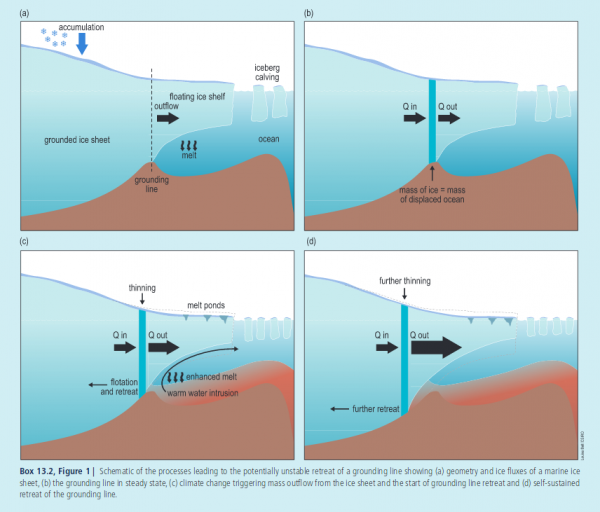

The MISI is based on a number of studies that indicated the theoretical existence of the instability … The most fundamental derivation, that is, starting from a first-principle ice equation, states that in one-dimensional ice flow the grounding line between grounded ice sheet and floating ice shelf cannot be stable on a landward sloping bed.

The AR5 also discusses a feedback effect concerning the grounding line and ice thickness and the consequence for the sea level (also see graphic below), but does not include the effect a sea level rise may have [FAQ 13.2, p. 1177]:

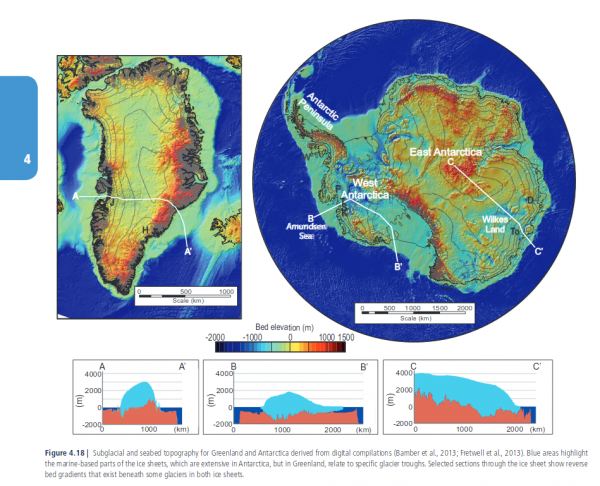

On bedrock that slopes downward towards the ice-sheet interior, this creates a vicious cycle of increased outflow, causing ice at the grounding line to thin and go afloat. The grounding line then retreats down slope into thicker ice that, in turn, drives further increases in outflow. This feedback could potentially result in the rapid loss of parts of the ice sheet, as grounding lines retreat along troughs and basins that deepen towards the ice sheet’s interior.

I also searched with Google scholar, without finding any answer. There may of course be studies about the effect that a sea level rise may have on the glacier calving that I have missed.

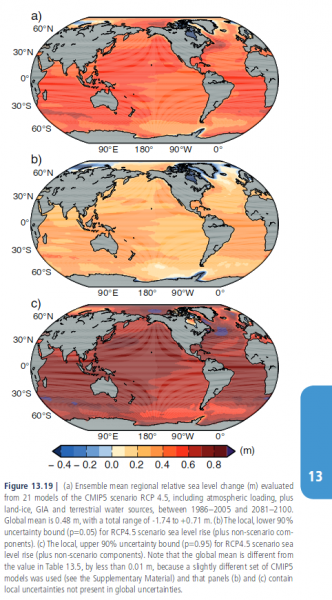

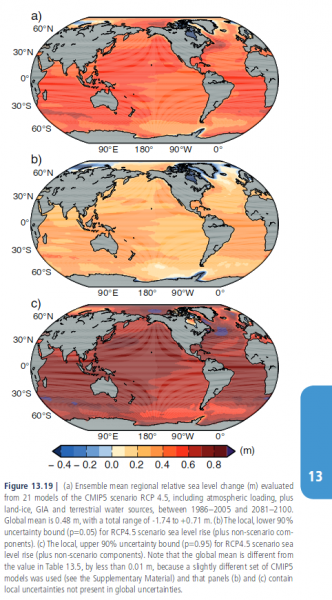

A reason why the scenario that I sketched out may be less important is that the sea level rise is expected to be smaller near the poles due to Earth’s redistribution of mass and the consequences for gravitational forces (see graphics below). But this is also a speculation as far as I know. What if the current situation is a result of a fine balance of forces over time that includes the buoyancy associated with past estate levels?

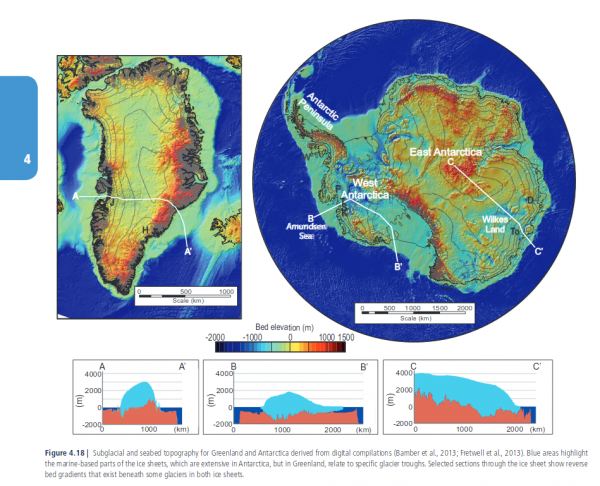

Any triggering effect that a sea level rise may have on the submerged ice sheets and glaciers buttressed by the ocean floor depends on the depth of the ocean floor and the thickness of the ice.

We can get a rough estimate of the reduction of the weight responsible for the friction: δF=ρgδh. Every cm sea rise corresponds to a reduction due to increased buoyancy for ice resting on the ocean floor of 1000kg/m3 x 9.8m/(kg s2) x 0.01 (m)= 98 N/m2.

The change in the net sum of forces caused by a sea level rise is expected to have little effect in most regions, except where the gravitational force of the ice sheet is close to being balanced out by the buoyancy.

An additional surge of ice into the ocean will further increase the sea level, which subsequently may affect the buttressing effect of the ice itself. Is there a triggering point beyond which a feedback process is put into action that will accelerate the disintegration of some of the ice sheets?

According to AR5 (graphics below), there may be some regions where a sensitivity to a sea level is not too unlikely, although this needs to be investigated in more details.

I cannot recall ever having seen or heard any discussion about the possible effect a rising sea level may have on the ice sheet dynamics. Hence, is there anybody who know of published work that is relevant to my question?

Progress happens through scientific discussions, calculations, formulation of hypotheses, and the testing of these, and this is our best bet to get closer to a true answer. And of course, others need to reproduce the same results independently. Convincing answers then result in a consensus.

Happy new year!

References

D.M. Holland, R.H. Thomas, B. de Young, M.H. Ribergaard, and B. Lyberth, “Acceleration of Jakobshavn Isbræ triggered by warm subsurface ocean waters”, Nature Geoscience, vol. 1, pp. 659-664, 2008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ngeo316

M.F. Meier, M.B. Dyurgerov, U.K. Rick, S. O’Neel, W.T. Pfeffer, R.S. Anderson, S.P. Anderson, and A.F. Glazovsky, “Glaciers Dominate Eustatic Sea-Level Rise in the 21st Century”, Science, vol. 317, pp. 1064-1067, 2007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1143906

On Thursday, January, 12, 2016 at 3:00pm EDT, William Hohenstein will discuss methods and opportunities for incorporating Climate Change considerations into programming for Extension personnel and other professionals who assist producers in their operations. This is an excellent opportunity to find out how USDA can help Extension use climate tools, information and programs to enhance programming.

On Thursday, January, 12, 2016 at 3:00pm EDT, William Hohenstein will discuss methods and opportunities for incorporating Climate Change considerations into programming for Extension personnel and other professionals who assist producers in their operations. This is an excellent opportunity to find out how USDA can help Extension use climate tools, information and programs to enhance programming.