NIFA-funded research used genetics to hornless dairy cattle. (Image courtesy of Recombinetics)

Our charge in the food and agricultural sciences is to move from evolutionary discoveries, which contribute to marginal changes over long periods of time, to revolutionary thinking to deal with ‘wicked’ problems by deploying transdisciplinary approaches that solve complex societal challenges. Similar to how the Internet-driven disruptive technologies have transformed America and the rest of the world, advances in data science, information science, biotechnology and nanotechnology can transform agriculture and our capacity to address societal challenges.

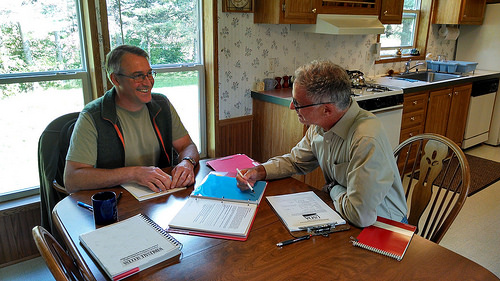

Advances in the field of genomics have helped breeders produce desirable varieties of crops and livestock and overcome challenges that had previously been undertaken via conventional breeding. For example, in the dairy industry, most cattle are mechanically or chemically dehorned early in life to protect against injury to other cattle and their handlers. To eliminate this bloody and painful process, a team of NIFA-funded researchers at Recombinetics have successfully used gene editing to introduce the hornless gene into the cells of horned bulls. While the majority of hornless cattle generated via conventional breeding produce low quality milk, gene editing offers a simple and rapid solution of generating hornless cattle that produce high quality milk.

NIFA-funded researchers at Iowa State University recently converted graphene—a recently discovered nanoscale material that is lightweight, strong, stable and perhaps better at conducting heat and electricity than any other material—into a form usable for real-world applications. The research team is using graphene to develop biosensors that can quickly and rapidly screen for multiple pesticides in a single field sample. Such biosensors could alert users of potentially dangerous levels of pesticides in water, soil or food products. Additionally, the graphene-based electronics offer tantalizing possibilities in “wearable” technologies that can potentially help address sedentary lifestyles and obesity.

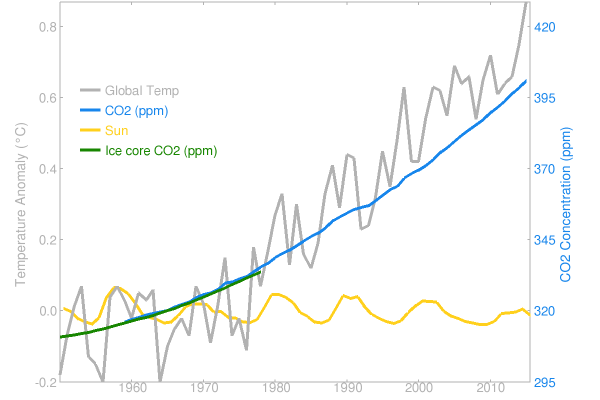

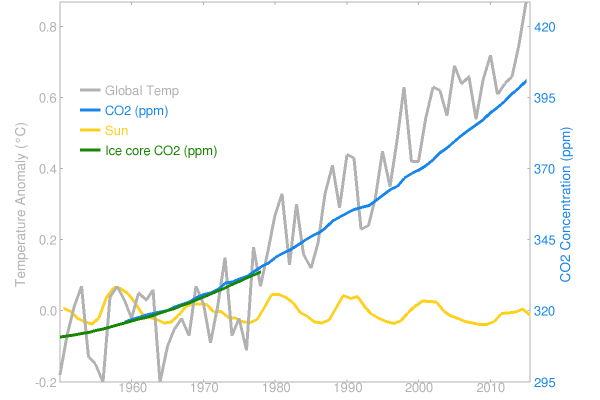

Strategically linking computer science, software engineering, statistics, business and economics with traditional agricultural researchers, extension agents and food producers will likely lead to better use of resources in the face of climate variability and pollinator decline. For example, increasingly sophisticated sensing and imaging technologies such as Lidar can help researchers investigate the relationship between habitat diversity and pollinator abundance, diversity and movement. NIFA-funded researchers at Oregon State University are developing miniature wireless sensors that can be worn by bumblebees and track movement and relative visitation rates to crop plants and surrounding habitat.

Advances in imaging technology are also making it possible to rapidly determine fruit count, size, and quality in the field. For example, a team from Carnegie Mellon University created a camera-equipped vehicle with the ability to detect fruit and conduct automated image analysis. This vehicle will improve the ability of fruit, berry, and vegetable growers to predict yield in advance of harvest so that they can adequately plan for harvest labor, shipping, storage, marketing, and sales.

NIFA hosted a Data Science Summit recently, which points to the potential for “big data” to address societal challenges by taking on and solving nutritional security, nutrient management, and “dead” zones in bodies of water due to excess nitrogen and phosphorus, climate change, water use efficiency, obesity, and other such wicked problems. The transformative developments in computational capabilities, predictive modeling, and machine learning offer tantalizing possibilities of the power of big data.

Already, these advances have catalyzed numerous transformative discoveries that will revolutionize how agriculture is practiced in the field. The future of agricultural data science involves linked, distributed data with multiple layers of accessibility and standards that evolve over time. Entire new fields and cross-sector business opportunities will form around this internet of agriculture, enabling farmers to provide for the next generation in a new world of opportunity.

Oct. 1, 2016, marked the seventh birthday of USDA’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA). Upon its establishment, NIFA committed to addressing the societal challenge of ensuring nutritional security in the context of climate change, diminishing land and water resources and environmental degradation. Over the last several years under the leadership of President Barack Obama and Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack, the agency has supported the development of various user inspired discoveries and inventions that are transforming lives throughout America.

Addressing society’s “wicked” problems, for which we have the knowledge and ability to solve, but aren’t able to because of lack of agreement on how to deploy the solutions, require transformative and revolutionary discoveries across multiple scientific, economic, industrial and political domains that can result in solutions across the food systems value chain. These efforts will require new advances in the myriad food and agricultural sciences, along with advances in information technology, biotechnology, nanotechnology, and data science. NIFA’s investments in these latter areas point to a future for disruptive knowledge to be able to solve some of the wicked problems.

NIFA and its partners and stakeholders have had great success and are poised and ready to undertake more such work and deploy the solutions to challenges people face.

NIFA invests in and advances innovative and transformative research, education and extension to solve societal challenges and ensure the long-term viability of agriculture. USDA has invested $19 billion in research and development since 2009, touching the lives of all Americans from farms to the kitchen table and from the air we breathe to the energy that powers our country. Learn more about the many ways USDA scientists are on the cutting edge, helping to protect, secure and improve our food, agricultural and natural resources systems in USDA’s Medium Chapter 11: Food and Ag Science Will Shape Our Future.