By Doyle Irvin, American Forests

Fence Row to Fence Row

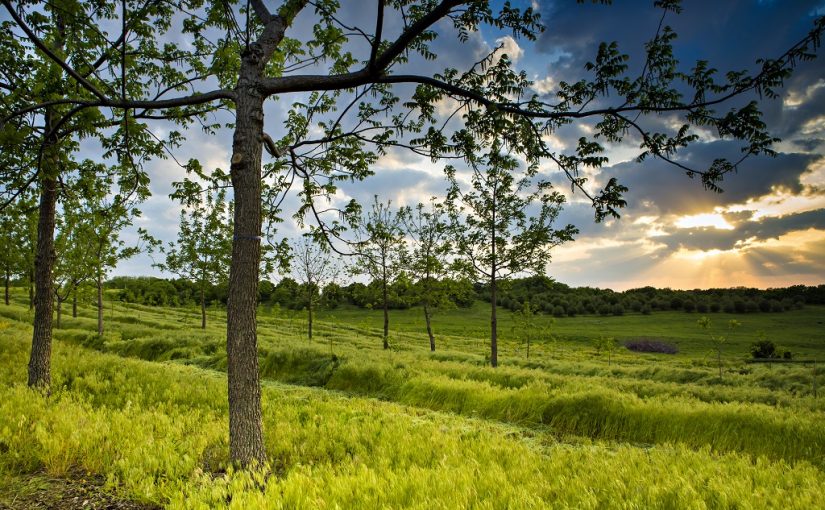

Lone tree in the midst of cornfields. Credit: Fred Jackson via Flickr.

In the early 1970s, a man named Earl Butz set a policy that would determine the shape of our nation for decades to come. As Richard Nixon’s secretary of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Butz famously encouraged farmers to “plant from fence row to fence row,”[i] maximizing all their available land into sellable crops. Cut your trees, turn them into timber. Plant corn. As he was notorious for saying, “Get big or get out.”

Dismantling New-Deal-Era regulations that were centered around preventing another Dust Bowl, Butz pushed for huge subsidies of corn and soy beans, promising farmers that their crops would be sold (to the Soviets) no matter the level of supply or demand. He promised that the United States would “feed the world.”

That he served on the boards for multiple agribiz conglomerates was less important to farmers at the time than the 1973 Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) oil crisis, which, in a sideways manner, drove grain prices through the roof. Because key crops like corn and soy had a guaranteed minimum price protected by the government in case the market crashed, farmers were incentivized to take advantage of the bull market and convert as much land as possible into these crops. By the time Butz was run out of town for making racist remarks publicly, the damage had already been done, and his policies outlasted his tenure in office.

These land conversions, as we will cover, lead to increased frequency and severity of super-floods — but it’s also important to keep in mind that there are a number of different factors at play here, so we can refrain from sensationalist finger-pointing.

The Scope of the Problem

Mississippi Flood, 2008. Credit: Todd Ehlers via Flickr.

The first thing we have to understand is the size of what we are dealing with. In simple terms, a catchment is the area from which rivers receive their water. All of the rain and snowmelt converges into a single area, forming a stream or river. The Mississippi River is the largest river in the largest drainage system in North America. Constituting roughly 40 percent of the landmass of the continental U.S., the catchment of this drainage system includes 31 states and two Canadian provinces, for a total of more than 1,245,000 square miles.

Consider the population explosion of the last century. At the time of the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, the population of the U.S. was 119 million. Today, we sit at 324 million. Because of guaranteed return on crops like corn, many of these new citizens moved to areas within the Mississippi catchment and started farming. Those people needed to eat; they needed dry land to build their houses. They needed roads, and they needed places to park their cars. Roofs, roads and parking lots are all far worse at water retention than natural areas like floodplains, wetlands or forests.

Prior to human intervention, the Mississippi had plenty of floodplains and wetlands that would take the runoff during flood season and prevent superfloods. Because we need space and because floodplain soil is rich in nutrients, humans have been constructing levees to create farmland adjacent to the river largely since 1800. [ii] The side effect is that each time a levee prevents the river from reaching a floodplain, it just sends all that prevented water further downstream. Today, in the middle and lower stretches of the Mississippi, the main stem of the river is no longer connected to 90 percent of its floodplain.

The levees protecting these urban areas and farms are often privately maintained and not adequate to really protect those areas. They are mostly built to protect from average or “99 percent” floods, and not from so-called 100-year floods that are now happening every other decade or so. For example, in 1993, 1,000 of the 1,300 levees on the Mississippi River failed.[iii]

It’s Not Just the River-Front Property

Memphis, Tenn. flood, 2011. Credit: Chris Wieland via Flickr.

When a wild area is converted into a farm, not only do the levees constructed to protect the farm make the flood larger for those downstream by preventing natural release points, they also decrease the flood absorption of the catchment at large. When trees are cut and replaced with corn, the soil no longer holds nearly as much water. A cornfield is simply nowhere near as good at retaining water as a forest.[iv] That means that rain that falls on the farm travels from the topsoil to the groundwater to the rivers much more quickly (and, therefore, dangerously). Something important to remember is that this still applies to fields that aren’t on the border of the Mississippi — remember the catchment covers 40 percent of the landmass of the continental U.S., so a forest being turned into a cornfield in the remoter hills of Minnesota affects flood water levels all the way down in the flats of Louisiana.

The soil, too, becomes more mobile, getting picked up by the wind and also moved around by rainfall, entering the groundwater and then eventually the river. As silt from erosion fills in the river bed, the average height of the river increases and makes the area more flood-prone. With that silt comes all the fertilizers and pesticides used to grow the crops.

The Price Tag

Agriculture Secretary Earl Butz and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republic (USSR) Minister of Agriculture Vlatimer V. Matskevich in December 1971. Credit: USDA via Flickr.

Because of these major factors, the Mississippi River is getting squeezed into tighter and tighter spaces, meaning that record breaking floods occur more and more frequently. The 1993 flood cost close to $15 billion, and since 2011, major floods have caused roughly $34 billion dollars in the U.S.[v] These numbers will just increase as our population increases, as further space that was once floodplain gets settled.

So, was Earl Butz really the bad guy here? The answer to that is no, not entirely. Land conversions and levee constructions have been occurring along the Mississippi for more than 200 years, and the first major public outcry about their effect on floods happened in 1927 — long before him. But, Butz was the one whose policies made it incredibly lucrative to convert all available land to flood-inducing corn and soy crops, and it’s his policies that are still in effect today.

In Part Two of this series, we talk about potential solutions and their benefits.

[i] http://grist.org/article/the-butz-stops-here/

[ii] http://all-geo.org/highlyallochthonous/2011/05/levees-and-the-illusion-of-flood-control/

[iii] http://www.nwrfc.noaa.gov/floods/papers/oh_2/great.htm

[iv] http://ec.europa.eu/environment/integration/research/newsalert/pdf/32si_en.pdf

[v] http://moneynation.com/u-s-floods-cost-34-billion/